New York City Latinos stand up against racism with Mariachi music

I wrote about a protest against Latino discrimination in New York City, accompanied by portraits and testimonials.

I wrote about a protest against Latino discrimination in New York City, accompanied by portraits and testimonials.

--- Solo exhibit in Medellín's Museo de la Universidad de Antioquia ----

Conversatorio y visita guiada: 19 de Abril

“Pasear Sae” abarca de muchas maneras mi trabajo de campo junto con uno de los pocos pueblos en el hemisferio occidental que cuenta con una extensa autonomía territorial, el Gunadule.

Hacia 1870, cuando Panamá formaba parte de Colombia, la comarca de Dulenega (nega significa casa o habitat) fue creada como una forma de cabildo para abarcar el territorio ancestral Gunadule desde la ciudad portuaria de Colón hasta la comunidad de Arquía en el Urabá chocoano, a las bocas del río Atrato. Acto seguido de la independencia de Panamá, este territorio fue fragmentando, dejando a la comunidad de Arquía y Caiman Nuevo (en el municipio de Necoclí, Departamento de Antioquia) por fuera de la provincia especial, la comarca de Guna Yala, que fue creada a partir de la independencia Guna en 1925. Esto nunca ha sido un verdadero obstáculo para el pueblo Gunadule, quienes son expertos marineros y muchos cuentan con doble nacionalidad, lo que facilita cruzar el Golfo del Urabá para visitar a sus “primos” o ya sea para representar el Congreso General Guna.

Este trabajo es el producto de 4 meses de trabajo de campo interactuando con la comunidad. El nombre de la exposición nace de una expresión utilizada por este pueblo: “pasear” junto con el verbo dulegaya “sae”, que significa “hacer”, esta significa tanto una caminata corta, un viaje, un trayecto, hacer visita o divagar sin rumbo aparente. Pasear sae, el desplazamiento en tanto práctica, discurso e institución, es también la razón por la cual los Guna logran mantener un contacto, una unidad lingüística y cultural considerable entre Colombia y Panamá. Ellos han incorporado el viaje a su modo de vida de tal forma que se ha convertido en el vehículo de su conocimiento ancestral y patrimonio cultural. Esta exposición da cuenta de esta forma de relacionarse en un mar libre de fronteras.

La exposición se podrá visitar en las instalaciones del Museo Universitario de la Universidad de Antioquia, partir de próximo 13 de marzo de 2018.

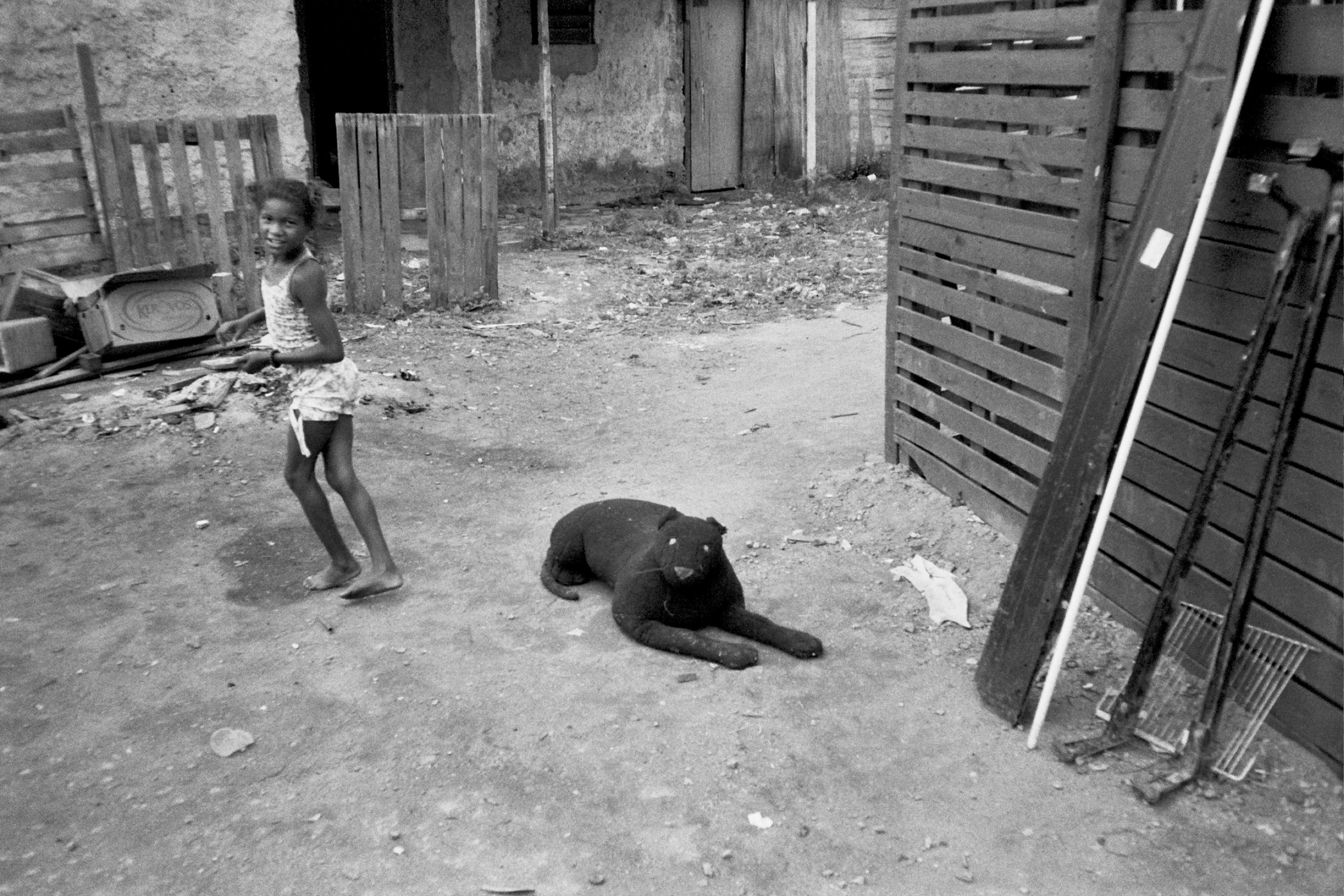

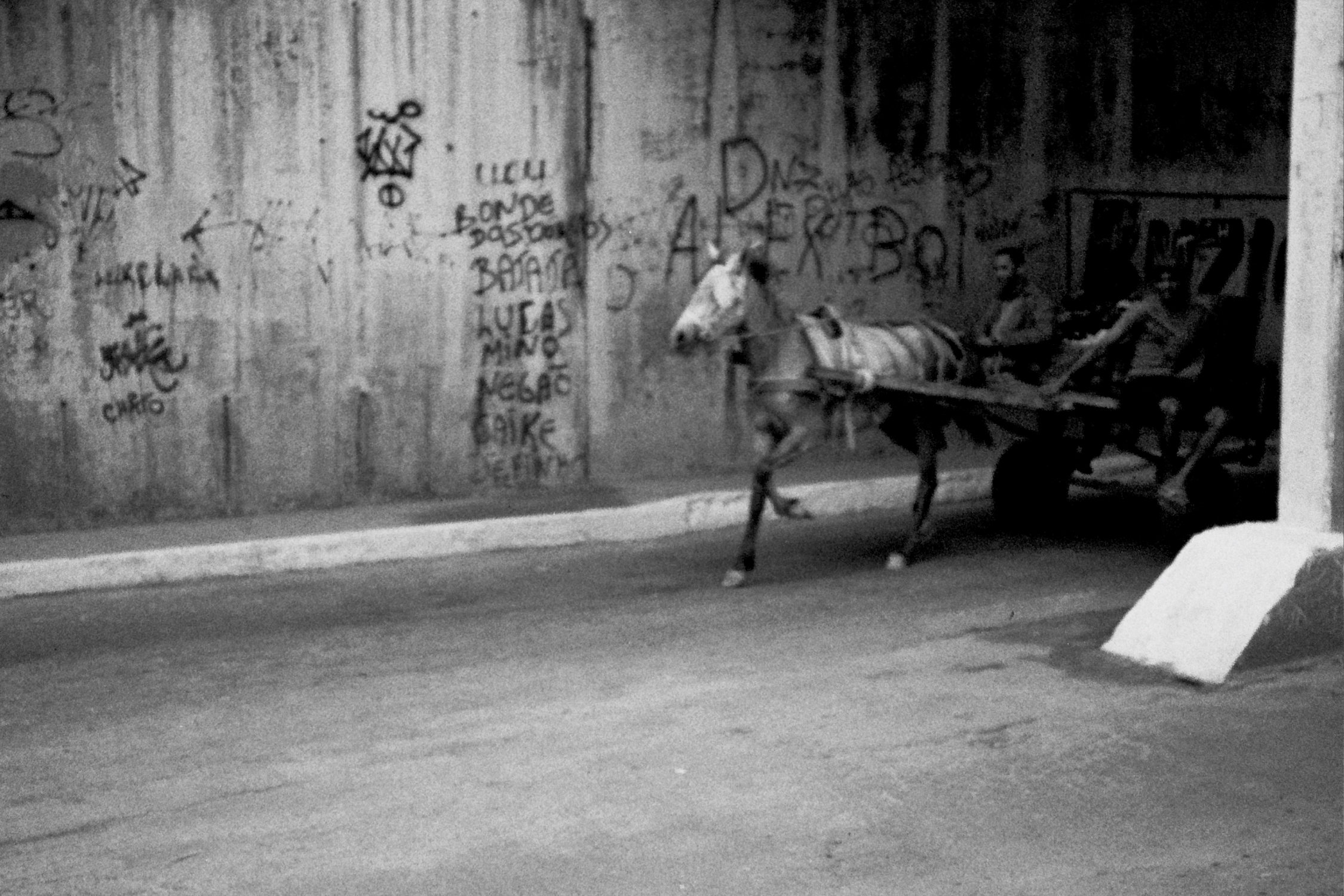

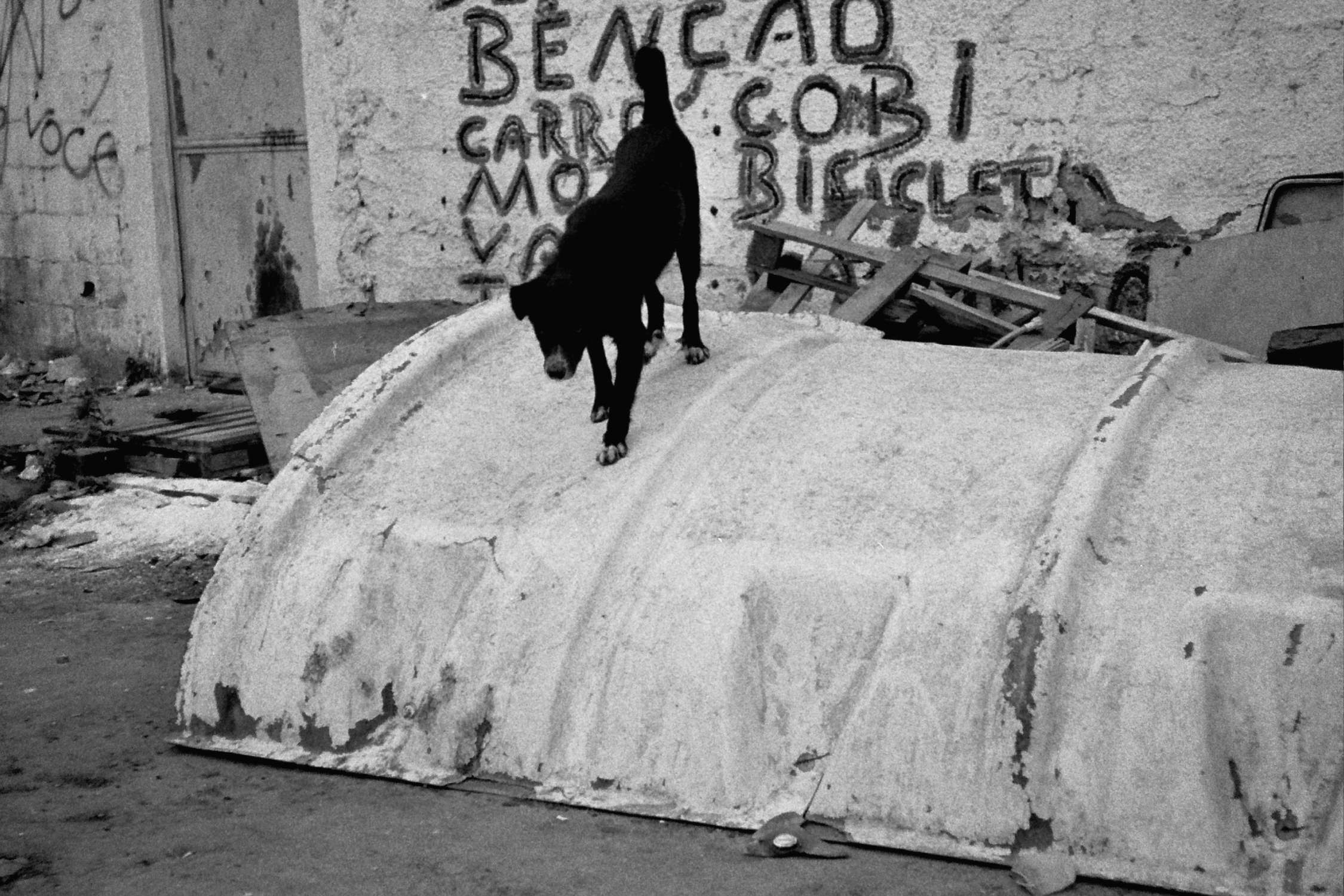

“Na Moita” is slang in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, for an action that cannot be carried out in the open. It literally translates to “in the bush,” and it is normally associated with delinquent activity, but also with anything unusual.

In the Baixada Fluminense – that is, the northern, most populous area of the Greater Metropolitan Area of Rio de Janeiro – life is often times at odds with city planning and other abstract notions, such as laws.

“Morar” is a Portuguese verb rich in connotations–it can mean “to reside,” “to abide,” “to live,” “to settle,” and “to occupy,” depending on the context–and it captures essentially the status of the inhabitants, or “moradores,” of these communities: some occupy, some others reside, few abide by the rules, and all live together thanks to interim agreements amongst themselves. For example, such is the case with the drug-dealing gangs that fuel the relentless confrontations with police, which have ended in blockades made of unused furniture.

Along with some students and staff from The New School in New York, I visited the Parque das Missões and Vila Beira Mar, two of the most prominent examples of slum habitation in Rio, according to local NGO Teto (which is known throughout Spanish-speaking Latin America as “Un Techo para mi País,” a Chilean transnational organization that mobilizes young volunteers to fight poverty).

Teto was there to accompany us throughout all the process. By association, people in the communities did not question much the fact that we were taking pictures, since the organization would always send media teams to document their housing intervention projects.

The living conditions were dire, electricity would disappear every time it rained, and the clogged drainage would cause major floods, not to mention serious sanitation issues. However forsaken the community seemed to our group, each individual that we spoke to was perfectly content with their community and the strong ties that bind it together: It was a settlement (or “assentamento,” which, in its etymology, signals to an agreement) that they all had created in the face of pressing difficulties. Needless to say, most assentamentos do not have a housing permit from the local prefecture.

Perhaps more importantly, community members also spoke of how dependent they were of “Bolsa Família.” This social welfare program was perhaps the centerpiece of the Lula administration, also part of the larger Fome Zero federal assistance program. It reduced poverty by 27.7% from 2006 to 2011, and is often described as the most impactful program of its kind in the world. It is now under threat by the large scale protests and court challenges against the Worker’s Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores) government.

Without Bolsa Família, the lives of the people of these neighborhoods would dire, and they would maybe be confronted with other decisions to be taken “na moita.”

These photographs, below, taken with a manual focus analog compact camera in black and white celluloid (a lot of focus hunting went on), are themselves as makeshift as the structures and situations that they intend to document; they portray the precarious material conditions and the way inhabitants bypass implicit or explicit norms to adjust to the ever shifting social dynamics, urban environments.

Stephen Ferry is an American photographer who has captured dangerous and tragic scenes of the Colombian armed conflict for twelve years. Ferry published a collection of his and his Colombian colleagues’ photos in a book titled “Violentology: A Manual of the Colombian Conflict.” Latin America News Dispatch interviewed Ferry at the International Center for Photography in New York about what he found most difficult to capture in the middle of a war, who the main protagonists are in his pictures and how photography contributes to Colombia’s peace process between the government and FARC rebels.Stephen Ferry is an American photographer who has captured dangerous and tragic scenes of the Colombian armed conflict for twelve years. Ferry published a collection of his and his Colombian colleagues’ photos in a book titled “Violentology: A Manual of the Colombian Conflict.” Latin America News Dispatch interviewed Ferry at the International Center for Photography in New York about what he found most difficult to capture in the middle of a war, who the main protagonists are in his pictures and how photography contributes to Colombia’s peace process between the government and FARC rebels.